It's pure coincidence that the beginning of my project coincided with the formation of the Coldengham Preservation and Historical Society. When I attended my first meeting I thought it was a long established organization firmly entrenched in all things Colden but it turns out they're putting together the bits and pieces of information much as I am. Of course, I started from zero and they possess lots of facts that I'm busy gathering but I'm hoping I also contribute and being part of the process is part of the fun. So with the help of my fellow Society members, I gather my clues and see what I can find.

It's pure coincidence that the beginning of my project coincided with the formation of the Coldengham Preservation and Historical Society. When I attended my first meeting I thought it was a long established organization firmly entrenched in all things Colden but it turns out they're putting together the bits and pieces of information much as I am. Of course, I started from zero and they possess lots of facts that I'm busy gathering but I'm hoping I also contribute and being part of the process is part of the fun. So with the help of my fellow Society members, I gather my clues and see what I can find. Friday, December 17, 2010

Sycamore

It's pure coincidence that the beginning of my project coincided with the formation of the Coldengham Preservation and Historical Society. When I attended my first meeting I thought it was a long established organization firmly entrenched in all things Colden but it turns out they're putting together the bits and pieces of information much as I am. Of course, I started from zero and they possess lots of facts that I'm busy gathering but I'm hoping I also contribute and being part of the process is part of the fun. So with the help of my fellow Society members, I gather my clues and see what I can find.

It's pure coincidence that the beginning of my project coincided with the formation of the Coldengham Preservation and Historical Society. When I attended my first meeting I thought it was a long established organization firmly entrenched in all things Colden but it turns out they're putting together the bits and pieces of information much as I am. Of course, I started from zero and they possess lots of facts that I'm busy gathering but I'm hoping I also contribute and being part of the process is part of the fun. So with the help of my fellow Society members, I gather my clues and see what I can find. Sunday, December 12, 2010

The Family Name

Since beginning this project last spring I have been searching for remnants of Coldengham. I’ve done research using histories, government records, maps and various letters and papers. I’ve visited known sites on the farm property and guessed at the boundaries. I’ve followed and photographed portions of Tin Brook and have tried to find old trees and other possible 18th c. candidates. I’ve also spent time with Jane Colden’s botanical manuscript and begun researching native plants.

Concurrently I’ve been looking at the farm from the other end of the story and have searched for contemporary traces of the Colden family while cataloguing the transformation of this part of the Hudson Valley. Looking at this land from two directions allows me to work backward as I also work forward through history, piecing together the story of Coldengham/Coldenham.

Saturday, December 4, 2010

Adelaide and Jane

Photographic Times was an illustrated monthly magazine devoted to artistic and scientific photography that began in 1871. In Volume XXXII from 1900 there is an article by Adelaide Skeel describing a camera field trip she made to Coldenham in search of the village and farm. Her article contains a description of her trip by trolley, the landscape in autumn and various facts about the activities of the Colden family. The larger part of the piece is a fantasy about a conversation she had with Jane Colden and a visit to the original home including the Cadwallader Sr. library and glimpses of the family coach "with yellow wheels". It seems Adelaide resorted to this device because on first viewing, there was little she could see of historic Coldengham. I can sympathize with her because 110 years after her article, Coldengham is even less visible. I can also thank her because she included a very helpful paragraph she found while reading a local history. It states:

Photographic Times was an illustrated monthly magazine devoted to artistic and scientific photography that began in 1871. In Volume XXXII from 1900 there is an article by Adelaide Skeel describing a camera field trip she made to Coldenham in search of the village and farm. Her article contains a description of her trip by trolley, the landscape in autumn and various facts about the activities of the Colden family. The larger part of the piece is a fantasy about a conversation she had with Jane Colden and a visit to the original home including the Cadwallader Sr. library and glimpses of the family coach "with yellow wheels". It seems Adelaide resorted to this device because on first viewing, there was little she could see of historic Coldengham. I can sympathize with her because 110 years after her article, Coldengham is even less visible. I can also thank her because she included a very helpful paragraph she found while reading a local history. It states:The buildings erected by the Coldens are thus enumerated: "the old stone academy house, Coldenham stone house on the turnpike, long, low house east of stone house at the foot of the hill, house known as the Thomas Colden Mansion north of the turnpike, two dwellings east of the last one named and the dwelling on the hill south of the turnpike, a homestead subsequently deeded by Colden to his son Cadwallader, Jr."I've already marked my map with the location of the original dwelling south of the turnpike with it's adjacent cemetery and also the stone house on the turnpike belonging to Cadwallader Jr. With the help of Suzanne Isaksen, Town Historian, I've identified the site of the Thomas Colden Mansion and it is now marked at the top of my map forming the most northern boundary of Coldengham I have found.

I've also received recent help from the members of the Coldengham Preservation and Historical Society including Joe Devine who has researched the Colden Canal. The southern two dots on my map represent known canal locations, one of which is located in the current day Stewart State Forest, south of Interstate 84 and the southernmost point of Coldengham on my map.

Adelaide Skeel took her camera with her on her excursion but none of her photographs appear with her article. Perhaps she was so discouraged by the changes she didn't take any pictures. Maybe I should take a hint from Adelaide but instead I'm feeling encouraged as I continue to look for Jane Colden.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Bloodroot

Jane’s detailed botanical descriptions reveal her curiosity and intelligence and her careful observation demonstrates the working of a scientific mind. For a woman of that time to be encouraged to follow an intellectual pursuit and to succeed in the field provides enough explanation for why Jane became the first woman botanist of colonial America. But as I read her entries I find some of them to be not only carefully observed but also erotic.

Stalk is moderately thick, round smooth naked, & grows about a

foot high, it carries a single flower, its top turn downwards so that

the flower hangs with its top downwards but when it is in Seed,

the Stalk stands erect again.

Flowers are of a pale yellow colour, grow from 3 to 10 together, at

The top of the Stalk, each having a separate foot Stalk, of about half

An Inch long, and bend downwards; when the Berries ripens their

foot Stalk become of a bright red colour, & also the under end of

those Leaves directly under them.

Botany is mostly about reproduction so maybe I’m just reading something extra into her writings but I wonder if botanical study provided Jane an avenue into another area off limits to women of her era. In pursuit of this idea I am producing a series of folios that include some of her descriptions. The folio shown here is titled Bloodroot and is made from pigment prints on handmade paper with pressed plants, silk organza and linen thread. It measures 32” x 54” when open.

Sunday, October 17, 2010

Holland and Cherryderry

Coldengham was largely self-supporting. The farm grew flax and raised sheep to produce linen and wool that was carded, spun and woven on site. The girls in the family learned to sew as well as knit and with occasional help from itinerant sewers and, I imagine, the family slaves, produced all of the everyday clothing. The ability of the farm to be self-supporting was probably also due in large part to the use of slave labor, mentioned in a letter of Alice Colden (Jane’s mother) from 1732 as “four Negro men and two wenches.”

Some fabrics were imported from abroad including Holland cloth, a fine linen sometimes striped with a colored cotton warp and named for the country where it was first manufactured. Holland was used for women’s dresses and men’s shirts and letters show that Jane’s father was sent 24 yards of Holland for that purpose by his aunt Elizabeth Hill. It has also been recorded that Governor Stuyvesant was christened in an “infant shirt, of fine Holland, edged with narrow lace.” In the Boston Records for the year 1760 “18 shifts one dozn of them very fine hollan” were listed as lost in the Boston fire attesting to the value placed on the imported fabric.

Cherryderry is a striped or checked woven cloth of silk and cotton and has various names including “charadary” and “carridary” which more closely reflect it’s origins in India than the further anglicized “cherryderry.” It was imported beginning in the late 17th c. and was used for women’s dresses and handkerchiefs. It was later manufactured in England but there are no references to it being worn at ceremonial events or mentioned much at all although it is part of a 1740 price list. There it sells for .31 per yard and is the least expensive of all the fabrics including coarse muslin. The only historical reference I find is of a runaway slave caught in Boston in 1728 while wearing a “narrow striped Cherrederry gown.”

Friday, October 1, 2010

Tin Brook

The name Tin Brook appeared in town records as early as 1774 and it has been suggested it came from an early Dutch landowner named John Tinne, Thinne or Tinbrook. If this is the case John probably would have been a neighbor of the Colden family given the dates, the length of the brook and size of the Colden property. Another possible source for the name is the combination of two Saxon words: tinn, meaning thin or small and broc meaning running water smaller than a river which seems a pretty good explanation. Whatever the origins of the name, it is still called Tin Brook and it's path is remarkably similar to that shown on early maps. I'm finding this to be very helpful as I follow it from the source in wetlands and vernal pools located to the south of current day Coldenham, making it's way past the original homestead and cemetery, on towards the houses of Cadwallader's sons and then meandering over to the Wallkill River to the west. As I navigate my way through residential developments, commercial sites and working farms to reach the brook, I find foundations, stone walls, and very old trees, some of which join Tin Brook as part of my Looking for Jane Colden collection. Although I haven't found any evidence yet, I keep an eye out for signs of the canal Jane's father built using the waters of the brook to move materials around Coldengham and establishing Tin Brook as part of the first canal in New York.

The name Tin Brook appeared in town records as early as 1774 and it has been suggested it came from an early Dutch landowner named John Tinne, Thinne or Tinbrook. If this is the case John probably would have been a neighbor of the Colden family given the dates, the length of the brook and size of the Colden property. Another possible source for the name is the combination of two Saxon words: tinn, meaning thin or small and broc meaning running water smaller than a river which seems a pretty good explanation. Whatever the origins of the name, it is still called Tin Brook and it's path is remarkably similar to that shown on early maps. I'm finding this to be very helpful as I follow it from the source in wetlands and vernal pools located to the south of current day Coldenham, making it's way past the original homestead and cemetery, on towards the houses of Cadwallader's sons and then meandering over to the Wallkill River to the west. As I navigate my way through residential developments, commercial sites and working farms to reach the brook, I find foundations, stone walls, and very old trees, some of which join Tin Brook as part of my Looking for Jane Colden collection. Although I haven't found any evidence yet, I keep an eye out for signs of the canal Jane's father built using the waters of the brook to move materials around Coldengham and establishing Tin Brook as part of the first canal in New York.Friday, September 3, 2010

3000 Acres

So exactly where was Coldenham? There are old maps with dates of 1749, 1755 and of course Cadawaller’s own map dated 1760, that have Coldenham clearly marked but give no indication of the boundaries for the 3000 acre patent granted to Cadawallader. I asked Joe Devine from Montgomery what’s known about the property lines and he said this is a question the Coldenham Preservation and Historical Society is trying to answer.

More recently I came upon a map created by Claude Joseph Sauthier that was published in 1779. This means that the map was being created in the years shortly after Cadawallader Sr. sold the entire property to his son. This map differs from its’ predecessors in that it is very detailed and focuses on property boundaries. Coldenham and its’ neighbors are identified, as are geographic details and the roads of that time period. Tin Brook can again be clearly seen and the east/west road running through the property probably closely follows present day Route 17K. I think the road running to the south is what is now named Maple St. seeing as it is the road closest to the site of the original Colden home. All this seemed really helpful until I started comparing the 1779 map to our satellite map and began to see how the proportions don’t match which makes sense given early mapping methods but is disappointing none the less.

I gave up the idea that I would be able to trace the property lines from an old to new map and decided the boundaries would slowly reveal themselves as I found more locations known to be part of the original property. I’ve marked what I currently know. The single red square shows the site of the Cadwallader Jr. mansion ruins and the pair of squares shows the family cemetery and my best guess at the location of the original Colden home.

Monday, August 30, 2010

No. 93

The Jane Colden manuscript containing her over 300 descriptions and drawings of Hudson Valley plants is held in the collection of the British Natural History Museum. In 1963 the Garden Clubs of Dutchess and Orange counties in New York published a reproduction of Jane’s manuscript with a selection of her original entries. It’s wonderful that we have this for reference and it enables us to read her detailed entries for the approximately 60 plants selected. Unfortunately the reproductions are somewhat crude and show none of the subtlety described by Dr. Karen Reeds, a Linnaeus expert, who spent an afternoon comparing the original with the facsimile. According to Dr. Reeds the original displays a delicate line quality and watercolor washes that have been lost in the reproduction. Fortunately Jane’s text is reproduced both in her original handwriting and in transcription, allowing her careful observation and powers of description to shine through. Her entry for Pokeweed concludes with the following:

Jane’s handwriting is beautiful and the handwritten pages permit me to imagine her at work carefully recording her observations. Unfortunately, the harshness of the 1963 reproductions prevent me from following this flight of imagination very far so, using her handwritten entries, I have made new pages for Jane’s manuscript. The page here is entry No. 93. Phytolacca decandra Poke Weed.

Friday, August 20, 2010

At Home

The American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the perfect place to look at colonial American furnishings. Besides the period rooms, there is open storage that translates into rows of glass cases filled with multiple examples of household furnishings. The computer banks allow for specific searches and when asked for what was made prior to 1800 came up with lots of examples of silver tankards and spoons, pewter plates and porrigers, all produced in New York City. There is also a decent sampling of Chinese import plates and platters and English porcelain that I would imagine Jane’s parents, being Scottish and also Royalist, might favor.

I was struck with how beautiful the objects are and realized I was responding not to the design but to the materials. Everything was metal, glass, wood, ceramic, or natural fibers. The computers were the only plastic objects to be seen.

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Father Daughter Botany

Thursday, August 5, 2010

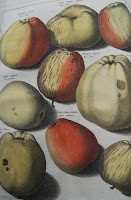

The Orchard

The Colden family cemetery once sat in an extensive orchard located to the east of the original Colden house. According to the letters and papers of Jane’s father the orchard produced cherries, pears, nectarines, peaches and later grew plum and apricot trees that were a gift from John Bartram. The apple varieties included Spitzenberghs, Newtown Pippins, Golden Russets, Pomroy, Golden Rennet and Kentish Codlings. The full name of the Spitzenbergh was probably Esopus Spitzenbergh, an apple that was found in the early 18th century in the Ulster County town of Esopus not very far north of Coldengham and very close to where I live.

Apple trees are grown either from seeds or by grafting. Seedlings often stray widely from their genetic origins producing an array of apple types often unusable for much besides cider of which American settlers drank a good deal. Sometimes, however, a seedling grows that produces a superior apple and that tree would be grafted to others to produce the now sought after apple. Esopus Spitzenberghs were such a type and it’s said to have been the favorite apple of Thomas Jefferson. Where this information comes from I’m not sure, but I do see the trees listed, amongst others, in his farm and garden diaries. The Colden family obtained both seedlings and apple scions for grafting from their Hudson Valley neighbors and ate the apples fresh, dried for winter, and turned into hard cider.

You won’t find Esopus Spitzenburgh or other evocatively named old varieties in your grocery store. Most commercial apples come from the same small group of parents making for uniformity in both genes and taste. This makes apples particularly vulnerable to attack, similar to the attack on the potato in Ireland in the 1840’s and eliminates the variety of tastes available from a diverse apple crop. Fortunately, there is a sea change taking place in the way we think about food and how it’s grown and distributed. In fact this sea change in many ways returns us to the way food was grown and eaten during Jane Colden’s life; producing diverse crops that are appropriate to the local climate and consuming it not far from it’s source.

It’s now possible to buy heirloom variety fruit trees in nurseries. In current nursery catalogues and foody websites the Esopus Spitzenburgh is described as aromatic, spicy and crisp, or having floral notes and hints of peach and perhaps pineapple. Sounds delicious. I wonder if Jane, having eaten this apple, would agree.

Friday, July 16, 2010

Mapping

A deed dated September 7, 1771 states “The honorable Cadwallader Colden, Esq, Lieutenant Governor of the Province of New York to his son Cadwallader Colden Junior, for natural love and affection and five shillings (description of land given)…excepting and reserving out of the same, the grave yard of four rods square, which is in the orchard to the east of the old mansion house…”

A deed dated September 7, 1771 states “The honorable Cadwallader Colden, Esq, Lieutenant Governor of the Province of New York to his son Cadwallader Colden Junior, for natural love and affection and five shillings (description of land given)…excepting and reserving out of the same, the grave yard of four rods square, which is in the orchard to the east of the old mansion house…”

Joe Devine, a Montgomery resident and author of various articles about the Colden family, found this deed documenting Cadwallader Colden’s sale of Coldengham to his son. The deed also describes the original Colden home as being west of the cemetery. A contemporary satellite map shows the still existing walled cemetery, now located on Pimm Farm in Montgomery, NY. It also shows Tin Brook and the curve where the brook shifts from east to north. A 1760 map places Coldengham to the west of the Colden Cemetery where Tin Brook Creek makes its’ turn.

Finding the location where Jane grew up and lived until her early 30’s feels like progress towards finding Jane. While the land has been tilled and altered since the mid 1700’s, it is remarkably, still a farm. Tin Brook still follows its’ natural path much as it did during her lifetime and if Jane were to walk here she might recognize this as the place she called home. This is even more remarkable if you consider our two methods of mapping. The map produced in Jane’s time is hand drawn, one-of-a-kind, and is based on slow observation and experience; the other is produced by a satellite located far above the earth and is available to anyone on the internet. 250 years has made for enormous progress in imaging which is amazing but perhaps to be expected. Unexpected to me was finding Pimm Farm and seeing Tin Brook make it’s turn through the property.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

A Proper Education

In 1728 Jane’s parents Cadwallader and Alice moved their household to Coldengham. There are various reasons given for the move including the desire to raise their children away from the temptations of the port city of New York, the need to develop the farm to help support the growing family and because of Cadwallader’s on again/off again career in politics.

According to the recent biography of Jane written by Paula Ivaska Robbins, transportation to Coldengham was difficult, depending upon the sloops that travelled the Hudson River between Albany and New York. All mail and supplies made the journey up the river and overland to Coldengham. In the winter all communication ceased. In spite of this isolation the Coldens provided a proper education for their children. Jane, and the seven siblings who survived past early childhood, learned from their parents the basic subjects of reading, writing and mathematics. In addition, books were imported from England and Europe to form a small library. The sons were groomed towards their eventual positions in government, business and the management of the family farm. The daughters were trained in the habits of virtue and economy, directed towards their futures as wives, mothers and household managers.

Jane apparently was a capable domestic manager. Her notes concerning the dairy, which was a major source of food and additional income, include detailed instructions for cheese making and a record of activities and sales. Walter Rutherfurd, a Scottish visitor wrote in 1758, “She makes the best cheese I ever ate in America.”

Sunday, June 27, 2010

The Oak

Yesterday morning I visited the site of the Coldenham ruins with Suzanne Isaksen, Town of Montgomery Historian and John Yrizarry, naturalist and interested citizen. Since we were with Suzanne it was a legal entry onto the property and we were able to make a leisurely tour of both the building and surrounding 8 plus acres. Following the current site map we saw the mansion and barn ruins and the remains of a cook house and various wells. We also walked around to all four edges of the property and discussed the various natural elements such as the wetland with narrow leaf cattail, the osage orange trees which must have been planted a good while after the house was built and debated which trees and plants should remain on the site. Since the Colden Mansion Heritage Park is only at the beginning stages many decisions such as the ultimate appearance and focus of the site have yet to be made.

Yesterday morning I visited the site of the Coldenham ruins with Suzanne Isaksen, Town of Montgomery Historian and John Yrizarry, naturalist and interested citizen. Since we were with Suzanne it was a legal entry onto the property and we were able to make a leisurely tour of both the building and surrounding 8 plus acres. Following the current site map we saw the mansion and barn ruins and the remains of a cook house and various wells. We also walked around to all four edges of the property and discussed the various natural elements such as the wetland with narrow leaf cattail, the osage orange trees which must have been planted a good while after the house was built and debated which trees and plants should remain on the site. Since the Colden Mansion Heritage Park is only at the beginning stages many decisions such as the ultimate appearance and focus of the site have yet to be made. My interest in the property is as a piece of the original patent of Jane's father Cadwallader. I'm assuming many native plants included in Jane's botanical manuscript continue to grow in the area and it will be interesting to compare her list with what we find in the ground. It would also be interesting to find out if any of the seed exchanges between the Coldens and other botanists have yielded offspring which continue to thrive.

As we finished our tour we stood looking at the northern property line when John noticed a tree standing on the lawn of the warehouse next door. He believes it to be a chestnut oak and speculated it was as much as 300 years old. While I'm not certain what type of oak it is, I would like to believe his estimate of its' age because it would be the only thing I've seen thus far that existed when Jane lived.

Thursday, June 17, 2010

Jane

This historic marker is located at the entrance to the East Coldenham Elementary School and is one of several in the area related to the Colden family. As the marker indicates, Jane Colden was a botanist and produced a manuscript of her research which is now housed in the British Museum. By the end of 1756 she had classified over 300 local Hudson Valley plants using the system developed by Linnaeus and produced the most complete flora of the region written by anyone before the 19th century. Jane corresponded with John Bartram, Alexander Garden, and other botanists of the era, apparently earning their interest and respect. The students that read this marker commemorating Jane's contribution to science probably walk the very same land where she did her work.

This historic marker is located at the entrance to the East Coldenham Elementary School and is one of several in the area related to the Colden family. As the marker indicates, Jane Colden was a botanist and produced a manuscript of her research which is now housed in the British Museum. By the end of 1756 she had classified over 300 local Hudson Valley plants using the system developed by Linnaeus and produced the most complete flora of the region written by anyone before the 19th century. Jane corresponded with John Bartram, Alexander Garden, and other botanists of the era, apparently earning their interest and respect. The students that read this marker commemorating Jane's contribution to science probably walk the very same land where she did her work.Sunday, May 30, 2010

Colden Mansion Ruins

The future Colden Mansion Ruins Heritage Park will be at the site of the ruins of the Cadwallader Colden Jr. estate. Cadwallader Colden Jr. was a brother of Jane Colden and built this home for his family on the grounds of his parent's farm. According to the historic marker it was built in 1767 which means Jane, having died in either 1760 or 1766 (there seem to be two dates) could never have spent time here. With what remains of the house, it's hard to imagine what it once looked like but it's possible to get some sense of the interior by visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art where the woodwork from the first floor west parlor has been preserved. It wasn't possible for me to walk around the ruins as they have been recently fenced off due to vandalism. I don't know if that was a problem before, but I imagine the new big green sign has encouraged this type of activity.

The future Colden Mansion Ruins Heritage Park will be at the site of the ruins of the Cadwallader Colden Jr. estate. Cadwallader Colden Jr. was a brother of Jane Colden and built this home for his family on the grounds of his parent's farm. According to the historic marker it was built in 1767 which means Jane, having died in either 1760 or 1766 (there seem to be two dates) could never have spent time here. With what remains of the house, it's hard to imagine what it once looked like but it's possible to get some sense of the interior by visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art where the woodwork from the first floor west parlor has been preserved. It wasn't possible for me to walk around the ruins as they have been recently fenced off due to vandalism. I don't know if that was a problem before, but I imagine the new big green sign has encouraged this type of activity.Coldengham/Coldenham

There still is a town of Coldenham near the Colden ruins although it doesn't consist of much more than the intersection of Coldenham Rd. and Rte. 17k. The most obvious traces of the family name are the Coldenham Fire Department and the Colden Manor, a banquet facility located at the traffic light. There were a few guys working on a car in the parking lot of the Fire Department and after taking pictures of the gleaming row of trucks, I asked them where the name Coldenham had come from. They didn't seem to know but one of them said there was something going on further down 17k and I should keep a look out for a big green sign. It's always interesting how names are absorbed into a community and while some people are interested in preserving local history, others are living their lives, in their town, no matter what the name.

There still is a town of Coldenham near the Colden ruins although it doesn't consist of much more than the intersection of Coldenham Rd. and Rte. 17k. The most obvious traces of the family name are the Coldenham Fire Department and the Colden Manor, a banquet facility located at the traffic light. There were a few guys working on a car in the parking lot of the Fire Department and after taking pictures of the gleaming row of trucks, I asked them where the name Coldenham had come from. They didn't seem to know but one of them said there was something going on further down 17k and I should keep a look out for a big green sign. It's always interesting how names are absorbed into a community and while some people are interested in preserving local history, others are living their lives, in their town, no matter what the name.